Costumes, candy, crunchy leaves, cawing crows. From the first time I wriggled into the black cat costume my mother sewed me for trick-or-treat, Halloween has been the most special night of my year.

This year leading up to All Hallow’s Eve, I treated myself to an audio version of Ray Bradbury’s The Halloween Tree dramatized by The Colonial Radio Theater. The voice acting is fun, but my favorite part was the music, which swelled, tremoloed, and tinkled in all the right places.

It’s been years since I last devoured The Halloween Tree. My first time through, I was absorbed by all the Bradbury goodness: boys, backyards, circus posters, kites, and the obsession (which I share) for ancient Egypt. Bradbury writes the vulnerable potential of childhood—and the delicious thrill of its impending end—with a tenderness that bores through my heart matter what stage of life I read it.

This second time around my focus was less on the childhood adventure and more on the crux of what Bradbury was exploring in this story: Halloween and the historical and cultural influences that brought it into being. Along the way, I searched for the reason that the spookiest night of the year has always been dear to my heart.

Light and life, death and darkness

Seven boys form the crew adventuring through the history of Halloween—not counting the elusive Pipkin, a friend in danger whom the boys hope to save. Each young man is costumed in classic Halloween fashion. Their individual costumes color each boy’s experience along the journey.

Bradbury doesn’t offer much backstory about the boys. All we really know about Fred is he’s dressed as an Apeman—a prehistoric man.

The boys’ adventure begins by highlighting humanity’s primal fear of the darkness. Their creepy travel companion, Moundshroud, asks whether being modern young men has cured them of fear of the dark. Their answer is no. Moundshroud probes uncomfortable places in our subconscious. The sun goes down. Will it rise again? How can we be sure? How long will it take? When we die, will it be like a night from which we never wake? On some level death is darkness with no promise of a sunrise.

The cyclical nature of being

On the next leg of their journey, Moundshroud whisks the boys to ancient Egypt, where focus is on Ralph, who’s wound in rags like a mummy. Moundshroud tells the tale of Osiris, which answers prehistoric man’s questions by drawing on the cyclical nature of existence. Darkness and light transform one into the other in an endless cycle. So, too, must life and death. Isis reuniting Osiris’s scattered body parts, Osiris’s influence on the Nile with its life-renewing flood cycles, and the mummification rituals of ancient Egypt, all serve to reinforce the idea that death is not the end, but a transformation, a passage through the cycle of life and death.

However, these old gods who teach us to respect the cycle of life and death are about to be displaced by new gods, and that’s the next leg of the journey.

Old vs. New Gods

Hank, dressed as a witch, leads the boys on a thrilling broomstick ride through literal and figurative darkness—a night in the Dark Ages. Bradbury plunges his young heroes into the long and messy history of old gods being supplanted by Christianity. It’s a messy history because those old gods never fully disappear. Their surviving devotees are stragglers—druids, conjurers, witches. Nor does Bradbury steer his broomsticks away from the brutal side of witch lore, when those who kept to the old ways were stigmatized, brutalized, and killed. Through Moundshroud, Bradbury reminds us these old gods with their old ways were more closely linked to nature and the seasons. Is it any wonder their power is heightened on the transition autumn represents, from the fecundity of summer to the dead of winter?

Evil spirits

The broomsticks become dead wood, and the boys land near Notre Dame. The Cathedral is a sort of headquarters for the New Gods, where gargoyles ward off broken remnants of those old gods, now known as evil spirits. Wally is the kid dressed as a gargoyle, but I adore this scene because in it Pipkin, who has been turned into a gargoyle, can only speak when the wind blows through his stone mouth.

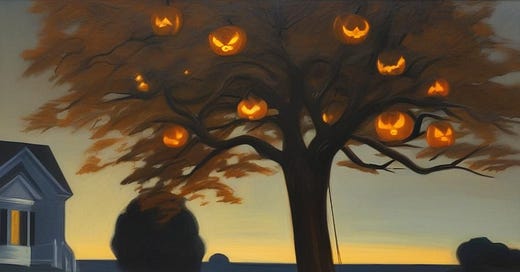

The gargoyles represent a new way of coping with fear of death, fear of darkness, fear of the unknown, which is to fight like with like—scare evil spirits away with ferocious supernatural guardians. It’s a similar idea to the leering jack-o-lantern we set to guard our porches on Halloween night. Doing something to protect ourselves makes us feel better.

J.J., a boy dressed as a devil, is also part of this journey. He shows how evil spirits—defined as defiers of the new Christian gods—engendered fear. They embodied sin and allowed humans a receptacle for their own dark nature, which they could then both condemn and explore outside themselves.

Lingering spirits

Old gods aren’t the only shadowy beings who lurk during a period of transition. Autumn is seen in many cultures as a period when the veil between life and death grows thin and the spirits of the dead wander among us.

George has donned a bedsheet to honor the tradition of ghosts. Exploring ghost traditions across different cultures shows the living at once remember and revere the dead, while fearing their otherness—particularly because spirits of the dead are often thought to linger due to a traumatic death. How to deal with such beings? Through appeasement. Lighting candles to remember them, leaving food out for them on windowsills, wearing costumes to hide from ghosts. It takes little imagination to draw the lines between these traditions and trick-or-treat.

Tom Skeleton (yes, that’s his name!) is the leader of the band of adventurers. He’s dressed in a skeleton costume, which echoes themes of the dead coming back to walk among the living. Here, the emphasis is less on the spirit—the emotions and moods still experienced—but on the gory nuts and bolts of our human form and what becomes of our bodies after we die. Moundshroud takes the boys on a graveyard adventure celebrating the Day of the Dead. Here, the link between the living and dead is both beautiful and haunting. As I walk around the neighborhood with my son, seeing zombie arms sticking out of the grass, and observing skeleton petting zoos, it isn’t hard to understand why a skeleton was chosen as the central figure for the Bradbury’s Halloween journey.

With change comes great excitement

Autumn has always been my favorite season. The falling leaves, the chilly evenings. There’s a feeling in the air that anything could happen.

The profoundest thing that ever happens to us as humans is death. In order to live, we must hold the knowledge of our mortality with incredible perspective. Joy is born from respecting our limited time, while living and loving as if we had all eternity to play. It’s a shadowy zone of human existence, one we can point to but not touch, and it bursts with power and potential.

Halloween appeals to my affinity for autumn and for the haunted and spooky. It’s a fantasy writer’s dream—infused with magic and half-forgotten traditions—the ultimate pretend play night. Halloween is both profane and sacred. During those delicious, spine-tingling hours between sundown and sunrise, nothing is safe. Halloween has no guard rails The thrill of danger and daring—not to mention the candy— make my blood sing. I could fly all the way to the moon.